President Trump’s focus on taking control of Greenland, a self-governing territory of the Kingdom of Denmark, has upset many in the Arctic.

Mr. Trump’s Greenland fixation is offensive to Aqqaluk Lynge, an elder Inuit statesman who once represented the Arctic population at the United Nations. Around 57,000 people live in Greenland, a population that’s largely Inuit, an indigenous Arctic people of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. Greenlanders have united behind a mantra: we are not for sale, but we are open for business. And Lynge offered up a defiant message of his own.

“If you should try something in the Arctic, you should be very careful,” Lynge said. “I think we should say, ice is slippery.”

Greenland, first settled by Viking adventurer Erik the Red around 982, has been part of the Danish Kingdom for around 300 years, though its capital — Nuuk — sits closer to New York than it does to Copenhagen.

The U.S. first discussed acquiring the territory, situated between North America and Europe, in the 1860s.

During the second World War, after Denmark was invaded by the Nazis, the U.S. was given control of Greenland. During that time, the U.S. built 17 military bases on the island. The most significant, Bluie West One in Narsarsuaq — located in the south of the territory, was a crucial stopoff before D-Day. The base was shut down in the 50s, but a military museum celebrating America’s presence remains.

After the war ended, President Harry Truman tried to buy Greenland for $100 million, seeing its location and resources, including its rich mineral deposits, as beneficial to defense of the Americas. Denmark declined, but the two countries did sign a treaty in 1951, which was amended in 2004 and still stands today — and gives broad license for the U.S. military to operate on the island.

Mr. Trump first eyed Greenland in 2019. The Prime Minister of Denmark called the overtures “absurd.” Since Mr. Trump has been re-elected, he’s been persistent in his desire to acquire territory and has declined to take military force off the table as a means to do so.

The administration maintains that it is essential for world security that Greenland becomes part of the U.S. Today, the Pituffik Space Base, which Vice President JD Vance visited last month, figures critically in U.S. anti-missile defense.

As ice caps melt and the Arctic trade routes and new sea lanes become more important, U.S. control, the administration believes, would thwart Russia and China’s presence in the western hemisphere. Mr. Trump has derided Denmark for not being up to the job of staving off potential threats.

“The routes are, you know, very direct to Asia, to Russia, and you have ships all over the place. And we have to have protection. So, we’re going to have to make a deal on that. And Denmark is not able to do that. You know, Denmark is very far away and really has nothing to do,” Mr. Trump said last month in the Oval Office.

But political scientist and University of Copenhagen professor Ole Wæver questions the premise of Trump’s aggressive stance. He’s unsure why the Trump administration is trying to acquire Greenland when America has always been so welcomed there.

“Bottom line is, the Americans are militarily on Greenland as much as they want,” Wæver said.

If Mr. Trump said he wanted to put up another base in Greenland, without buying, annexing or seizing the land, he wouldn’t get a no, Wæver said.

A growing number of people fear severe repercussions if the U.S. acquires Greenland by force. It could rewrite the world of international relations if the U.S. annexes Greenland, Wæver said.

“It is just a violation that is just one bridge further than anything we have seen so far,” Wæver said.

Apart from geo-strategy, the U.S. has offered another reason for acquiring Greenland: the untapped minerals. Trump’s inner circle portrays Greenland as packed with commodities and natural resources essential for the future world economy, such as gold, zinc and copper.

But getting access to them, like getting to anything else in Greenland, is a mission in itself.

Eldur Ólafsson, CEO of Amaroq Minerals, invited 60 Minutes to visit Nalunaq gold mine—one of the two active mines in Greenland. Mines across the territory have come and gone over the centuries, largely because of the logistical challenges. With gold prices at all-time highs, Ólafsson estimates that with prudent planning and patience, there is $150 million a year to be made from Nalunaq.

There may be gold in Greenland, but geologists 60 Minutes consulted with, in both the U.S. and Greenland, said that the promise of a Greenland natural resource jackpot is not the case. Plenty of countries — America included — have just as many, if not more, untapped minerals.

Mr. Trump’s focus on acquiring Greenland has left its citizens scratching their heads, Wæver said.

When Mr. Trump first expressed interest in Greenland, which has a history of welcoming the U.S., it fueled a spirit of independence. It also prompted locals to reassess their relationship with Denmark, which pumps around $800 million a year into Greenland’s economy, but also, historically, imposed its values on Inuit culture.

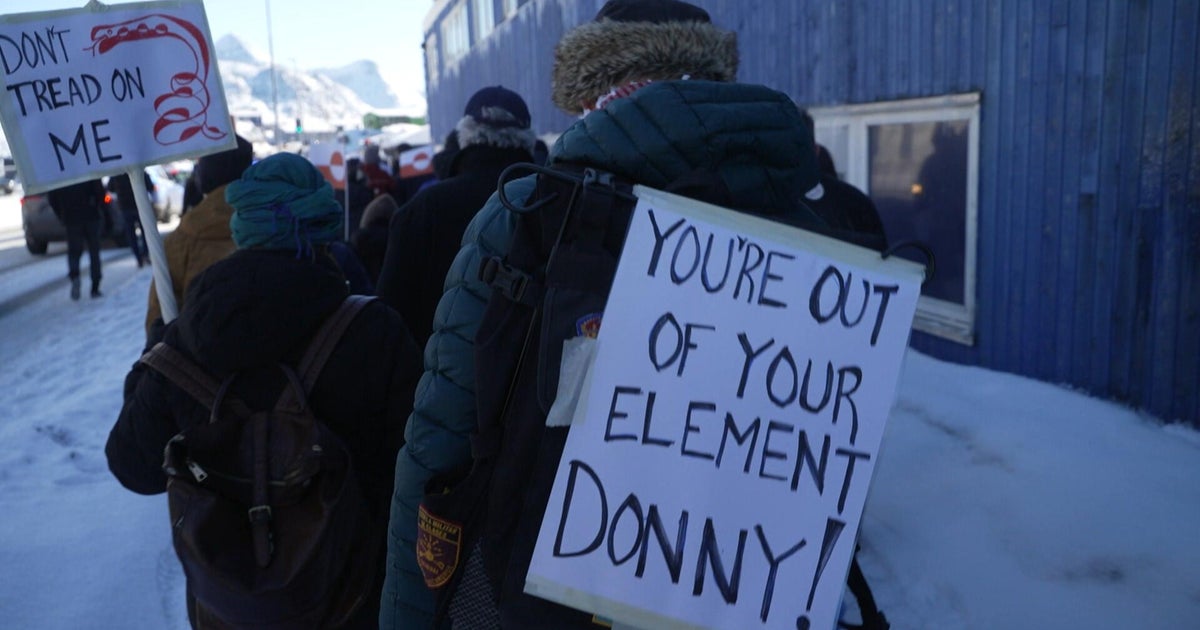

In the country’s capital Nuuk, population 20,000, thousands turned out last month to demonstrate against U.S. plans to acquire Greenland.

“It’s all clear that we stand together. No matter what political color you have,” Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen told 60 Minutes at the rally. “Greenland is for Greenlanders, not for anybody else.”

Maliina Abelsen, a former finance minister and native Greenlander, described the relationship between Denmark and Greenland as a forced marriage, at least on Greenland’s side. Mr. Trump expressing interest, she said, is like “a lover coming into the relationship.”

“I think that some people got a little attracted and they thought, ‘Ooh, that could be much better. That lover looks so rich and powerful,'” she said, but added: “We have also seen how our Inuit cousins live in Alaska, and how they were treated.”

It’s not a road Greenland wants to go down, she said. Per one recent poll, just 6% of the local population favors U.S. control.

The spotlight thrown onto her homeland has been overwhelming, Abelsen said.

“It’s intense because the whole world order is changing,” she said.