Microchips implanted into the back of the eyes of legally blind patients have helped some of them read again, according to a new study published Monday.

Out of the 32 patients with geographic atrophy — an advanced form of dry age-related macular degeneration — who completed the clinical study, 26 of them showed “meaningful improvement in visual acuity from baseline” 12 months after receiving the implant, the research published in the New England Journal of Medicine said.

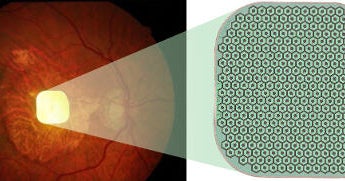

The treatment involves inserting a tiny implant thinner than human hair under the retina. Patients then have to wear specia glasses, which have a video camera and project what it sees via near-infrared light to the implant. The implant-glasses combination is called the photovoltaic retina implant microarray, or PRIMA.

One of the people who received the treatment, 70-year-old Sheila Irvine, told CBS News partner the BBC it was “out of this world” to be able to read and do crosswords again.

“It’s beautiful, wonderful. It gives me such pleasure,” Irvine said. “Technology is moving so fast, it’s amazing that I am part of it.”

While Irvine’s improvement is dramatic, it still requires a lot of concentration for her to use the PRIMA glasses, the BBC reported. She needs to put a pillow under her chin to steady the camera and it can focus on just a few letters at a time. Letters like C and O are also hard for her to distinguished without switching to magnification mode, according to the BBC.

Geographic atrophy, which affects some 5 million people wordwide, is the leading cause of blindness in older people. Until recently, there had been no treatment to improve patient’s abilities to read or recognize faces, the study’s lead author Frank Holz said.

“The achievement previously was pharmacological treatment, which slows down the progression, the expansion of the atrophic areas in the retina,” Holz, a retina specialist based in Germany, told Modern Retina at a conferences of retina experts last week.

In 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Syfovre, the first drug aproved to treat geographic atrophy. It’s administered with an injection and can slow the progression of the disease, although it does not reverse it.

There are two forms of macular degeneration: wet and dry. The wet form causes abnormal blood vessels to grow under the retina, causing scarring on the macula — which is located in the center of the retina. It impacts 15% of people and a treatment option has been on the market for many years.

The dry form is more common and causes the macula to get thinner and tiny protein clumps called drusen to grow. Until the FDA approved Syfovre, no treatment existed.

“But now with this device, a 2-by-2-millimeter implant, which for the first time restores visual acuity in those patients who are so advanced that they have lost completely their central portion, their central vision, in their retina,” Holz said.

CBS News chief medical correspondent Dr. Jon LaPook noted that while the device can help some people with geography atrophy, the clinical study is small.

The PRIMA implant, made by California-based biotech Science Corporation, is also not yet licensed and isn’t available as a treatment outside the trials, the BBC reported.

“This breakthrough underscores our commitment to pioneering technologies that provide hope to patients in need, and which have the ability to transform lives,” Max Hodak, founder and CEO of Science, said in a news release Monday. “We are excited about the potential of PRIMA to redefine vision restoration for these patients.”