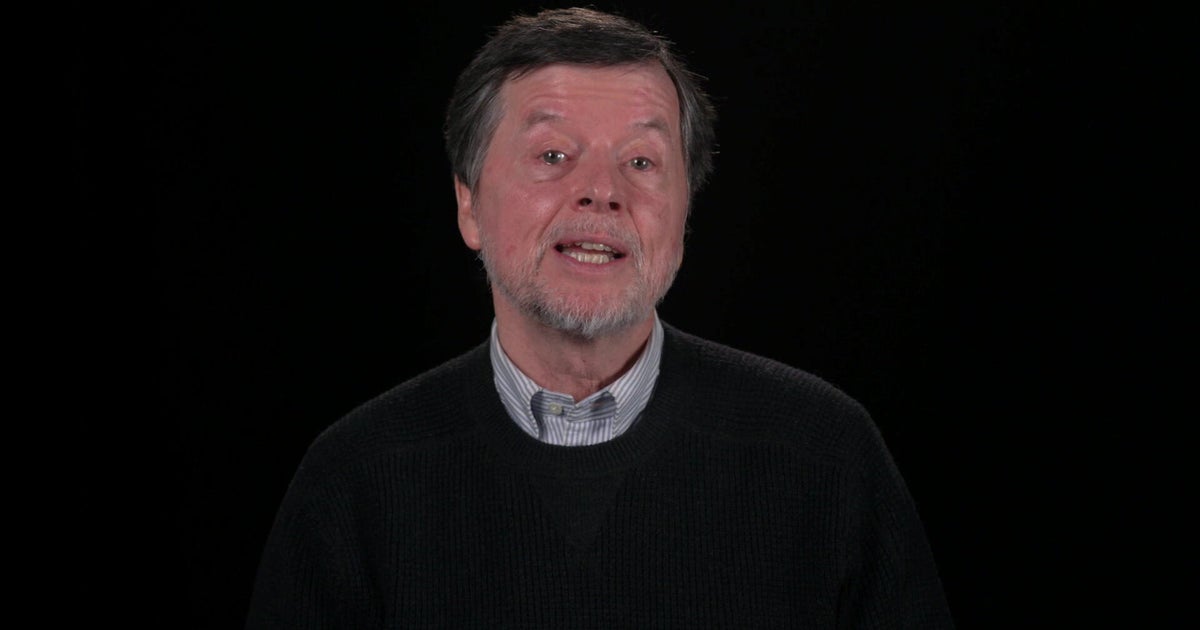

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, the famed civil rights leader who marched alongside Martin Luther King Jr. and later ran for president, has died, his family says. He was 84.

He died peacefully on Tuesday morning, surrounded by his family, they said in a statement.

Jackson was hospitalized for observation in November, and doctors said he’d been diagnosed with a degenerative condition called progressive supranuclear palsy. He revealed in 2017 that he had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, which affects the nervous system and slowly restricts movement and daily activities. Jackson called it a “physical challenge,” but he refused to let it prevent him from continuing his civil rights advocacy. His father, Noah Lewis Robinson Sr., also had Parkinson’s and died of the disease in 1997 at the age of 88.

Long known for his activism and political influence, Jackson spent his life dedicated to pursuing civil rights for disenfranchised groups both in the United States and abroad.

As a young man, he became a member of King’s circle and was with King when he was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1968.

That same year, Jackson was ordained by the Rev. Clay Evans, though he had dropped out of Chicago Theological Seminary three credits shy of a degree in order to work in the civil rights movement with King. He was later awarded a Master of Divinity degree in 2000 from the seminary, based on his life’s work and experience.

Over the years, he received over 40 honorary doctorate degrees from top universities across the country, according to the Rainbow PUSH Coalition, the Chicago-based organization he led for decades.

Jackson was born in Greenville, South Carolina, on Oct. 8, 1941. His mother, Helen Burns Struggs, was 16 and unmarried and gave him the name Jesse Burns. In his teenage years, his mother married Charles Jackson, and Jackson took his new stepfather’s surname.

In high school, Jackson was an honors student, according to Stanford’s King Institute, which helped him win a football scholarship to the University of Illinois. He studied there before transferring to the Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina, where he graduated in 1964.

As the civil rights movement grew, Jackson became involved in local activism. In 1960, a push to desegregate a local public library led Jackson down the road to become a leader in student-led sit-ins. After his graduation, he left his studies at the Chicago Theological Seminary to join King in Selma. There, he asked for a position with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a group of religious leaders led by King that focused on nonviolent protests and demonstrations, according to the Rainbow PUSH Coalition.

“This conference is called because we have no moral choice, before God, but to delve deeper into the struggle — and to do so with greater reliance on non-violence and with greater unity, coordination, sharing and Christian understanding,” King wrote about SCLC in 1957.

Jackson, with the support and trust of King, helped lead SCLC’s Chicago chapter and spearheaded Operation Breadbasket, a community empowerment campaign. His age and ambition led to numerous fights with leadership, including several arguments with King himself, according to Stanford’s King Institute. King and Jackson reconciled in 1968 in Memphis as they gathered for another civil rights protest.

In a now-famous photograph from that fateful time, Jackson stands to the right of King and fellow leaders Hosea Williams and Ralph Abernathy on the balcony of Memphis’ Lorraine Motel. The next day, at almost the exact same spot, King was assassinated by a gunman.

Following King’s death, Jackson was unable to reconcile with the SCLC. Instead, he founded PUSH, a Chicago organization whose name stands for People United to Save Humanity. In 1984, he also founded The Rainbow Coalition, which focused on social justice through voter engagement and representation. The two organizations merged in 1996.

The same ambition that chafed SCLC leaders also led Jackson to make a run for the Democratic Party’s nomination for president in 1984 and 1988.

Jackson received 18% of the primary vote in 1984, placing third overall and winning several states. But his campaign was marred by controversy over an antisemitic remark he made about New York’s Jewish community in a Washington Post story. Former Vice President Walter Mondale ultimately went on to win the nomination and lose to Republican incumbent President Ronald Reagan.

Yet even without holding office, Jackson continued to stand as a major political figure, championing the release of foreign nationals held in Kuwait in the lead-up to the Gulf War, becoming a “shadow senator” to lobby for statehood for Washington, D.C., and working as a special envoy under President Bill Clinton.

In 2000, Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Jackson is survived by five children with his wife of more than 60 years, Jacqueline, another daughter, and countless figures who were inspired by his leadership.

On election night in 2008, when Barack Obama was projected to win the presidential election, Jackson was captured on camera with tears in his eyes. He told CBS News that the moment America elected its first Black president brought him back to the struggles of the civil rights movement.

“To get here, we’ve gone through some bloody trails of terror to get here. Some good people — I think about the two Jews and the Black kids just wiped out,” Jackson said, referring to young civil rights workers murdered in Mississippi in 1964. “Medgar Evers, Dr. King at 39. We paid a price to get here.”